IV. DESCRIPTION OF THE CHANTILLY CODEX.I must interrupt this translation briefly so as to address the riddle about the manuscript's reference to Luchino Visconti as a key to the dating of the work. This first bit was written before Luchino's death in 1349, but then his name was scratched out; so it wasn't turned over to any Visconti until after 1349. Given that Bruzio is the consistently named dedicatee, and that he was nowhere near Bologna, after his father's death, until 1355, this deliberate cancelation must have happened after 1349. When the codex was completed is another matter. I don't know whether the mention of Luchino means that it was started while Luchino was alive but completed later, or that it was completed before Luchino died. Scholars since Dorez have decided that it was completed before Luchino's death, i.e. 1339-1349; see Julia Haig Gaesser, The Fortunes of Apuleius & the Golden Ass, p. 84, at http://books.google.com/books?id=fOq28aY4QUUC&pg=PA84&lpg=PA84&dq=Bruzio+Visconti&source=bl&ots=4Ev2ONc8tZ&sig=8osj2GywW-Ln8w-LDIRfGSsiVG8&hl=en&sa=X&ei=si4iUKOqLfP9yAGepYDIDg&ved=0CHQQ6AEwDA#v=onepage&q=Bruzio%20Visconti&f=false. She cites p. 560 of G. Orlandelli, "Bartolomeo de' Bartoli," in Dizionario biografico degli Italiani 6 (1964), pp. 559-560. But I am not convinced. Bruzio wasn't "miser Bruzio" until after 1349. Perhaps Dorez will have more information.

It is now time to describe the precious codex of the Museo Condé.

The format is in folio (0.333x0.226), written on parchment, and tied in red velvet; it consists of 20 pages, adorned with 20 large watercolors and painted initials. The rubrics are in Latin, the text Italian. Here's the title: [i] Incipit cantica ad gloriam et honorem magnifici militis domini Brutii nati incliti ac illustris domini principis Luchini (this name was deliberately canceled) Vicecomitis de Mediolano, in qua tractatur de Viriutibus et Scientus vulgarizatis. Amen.

I continue. Here I translate the Italian word "stanza" as the English "stanza" rather than its usual equivalent, "room", since each "stanza" is said to have 21 verses, which would not normally be true of rooms.

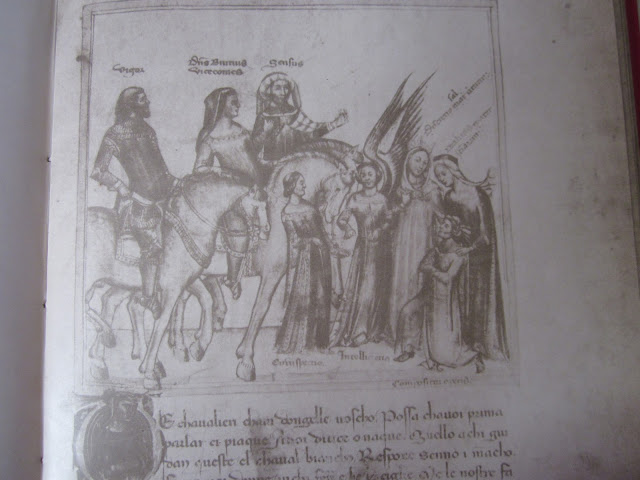

The Song is divided into two parts, each of which consists of nine stanzas, twenty-one verses each, and a coda (conogedo = discharge). The first part contains the description of Virtue, the second that of Science.I interrupt here to give this illumination. The one in color I linked to before, with poor resolution, is at

In the initial stanza the author declares his purpose, to describe in words of vulgar rhyme the daughters of Discretion, mother of the virtues, and those of Docility, mother of the Sciences. The second stanza contains an invocation to St. Augustine, from which will be derived the Latin rubric of each stanza of the song. The eight other stanzas are devoted to Theology, Prudence, Fortezza [i.e. Fortitude or Strength], Temperance, Justice, Faith, Hope and Charity. The first part ends with the coda, before which, as a kind of summary of everything, is a family tree.

The second part describes the Sciences: Philosophy, Grammar, dialectic, Rhetoric, Arithmetic, Geometry, Music, and Astronomy or Astrology. It ends, like the first, with a coda in which the author is named (Bartolomeo da Bologna di Bartoli), adding that he painted this volume for Messer Bruzio Visconti.

Each of the pages devoted to Virtue and Science is divided into three parts: on the top is transcribed the definition of the Virtue of Science, extracted from the works of St. Augustine; in the middle is seen expressed in color the representation of the Virtue or Science; the last, on the bottom, has the stanza dedicated to the Virtue or Science itself.

22 LEONE DOREZ

PART ONE - The Seven Virtues.

Folio 1r. - Under the title of the work, with marvelous art, is a scene, in which you see at left, three knights, the first called Vigor, the second Dominus Brutius Vicecomes; and third, with the doctor’s cap, Sensus[Judgment, Good Sense]. Before the horse of Bruzio are two women, Circumspectio (mantle in red and green, edges blue, green wrap around her head), and Intelligentia [Intellect] (dressed like her neighbor, except the edges), the latter supplied with two large wings, guiding the bit of the horse of the young Visconti in front of whom a man is kneeling, the compositor operis, Bartolomeo di Bartoli. Next to him are found two other women: the first, with the crown on her head, is Discretio, mater or sal Virtutum (white veil, blue robe and green mantle), the second, older, who puts her left hand on the shoulder of the poet, is called Docilitas, mater Scientiarum (red dress with blue sleeves and green cloak, headpiece red and white).

http://www.allposters.it/-sp/Chansonne-des-sept-Vertus-et-des-sept-Arts-liberaux-destinee-a-Bruzio-Visconti-Posters_i7303658_.htm. My black and white photo--not very good but the writing can be made out, is below:

As there is sometimes discussion of why, in the tarot, only Temperance has wings, be sure to notice here that out of these three primary virtues--Intelligentia, Discretio, Docilitas--only one, Intelligentia, has wings. It is not even the most important virtue, who as mother to the rest would be Discretio. I see no general convention as to the giving of wings. I resume.

The first knight, Vigor, on a dappled horse, has long hair, full beard, and above his coat of mail wears a robe half red and half green. One who compares this figure with those famous portraits that have come down of Bernabo Visconti (and particularly the famous equestrian statue admired under the portico of the Ducal Court in the Castle of Milan) will not hesitate to recognize here represented the future husband of Queen Della Scala. If, as we believe, this identification corresponds to the truth, it is very important, as we shall see below, to determine the exact date of execution of our codex.This particular stanza of medieval Italian is too hard for me, perhaps because it is a colloquial dialogue. I don't think it matters much.The later stanzas I can more or less understand, but not this one. The interesting parts are yet to come. I continue. I looked elsewhere in Dorez, to see whether he said anything of interest later on the material on page 1 of the manuscript. One thing was his characterization of Discretio, Bartolomeo's "mother of the virtues". Here is Dorez pp. 59-60:

Of a very gracious face and attitude is Bruzio Visconti, who, beardless, of almost feminine beauty, his body a little back, head bowed and covered with a red hood that goes over the bare neck and shoulders, puts his right hand quietly on the back of Bernabo’s and his left on the neck of his own white steed. Of this horse the right leg, the only one that I can see, is very poorly designed, excessively long and rigid, as are the rest, as the front legs of horses almost always are in the paintings of that century.

The third rider, who wears on his head a white and blue doctor’s cap, under his red cloak a green gown, with the hems of the sleeves red, raises both hands in the act of speaking. Who is this doctor of laws? Almost certainly we can identify him as Franceschino de' Cristiani, a Pavian judge, who in 1349 was sent by Luchino to assist the son in the siege of Genoa. In this expedition Rinaldo degli Assandri, a knight of Mantua, had acted as executor; the counselor was Christiani. So in the first we see the "Hand," and in the second, “Judgment.”

THE SONG OF VIRTUES AND SCIENCES 23

I said that the doctor raises his hands as a man who speaks, and in fact, as is clear from the first room of the song, he speaks to Discretion and Docility, who for their part want Bartolomeo di Bartoli to describe their daughters, that is, the Virtues and Sciences, to Bruzio. The poet, far from rejecting the offer, gives them full satisfaction, helped by texts extracted from the works of St. Augustine, to do the job he then will offer to the two Visconti:

Text of the first stanza.

"De, chavalieri, ch'avi dongelle voscho,

Possa ch’a voi prima parlar ci piaque,

A noi ditice o' naque

Quello a chi guidan queste el chaval biancho.”

Respoxe Senno: "I’ mancho

Senza voi, donne, in chi ferme ho le ciglie;

Mo le nostre famiglie

Intelligentia et Acchorteza parme,

E che Vigore in arme

Ben cognoschai; per certo in voi il cognoscho;

El chavalier eh' è noscho.

Chiamato è miser Bruze “; e si i compiaque;

Discretion non taque.

Né han Docilità chi v' è dal fiancho,

Vegiendo el baron francho;

Ma dissenme ambe due per miraveglie:

“Descrivi a lui mie figlie

In rima per vulgare”. E satisfarme

Conuen loro et aitarme

Choi testi d'Agustino e farmen ponti;

Poi darle in man di dui magiur Veschonti.

Alla dottrina agostiniana, già fin dal secolo XII nettamente espressa ne' libri di Ugone di San Vittore e largamente divulgata nel secolo seguente per mezzo dei florilegi, aveva di certo attinto anche Bartolomeo di Bartoli, e se l'era presa senza mutarne nulla, se non che all'Umiltà, radice delle Virtù, sostituì la Discrezione, madre o sale delle Virtù, cioè probabilmente la facoltà di discernere il bene dal male, la Virtù dal Vizio.I wonder if that last doctrine, too, can be found in Augustine. I don't know, but I will keeping my eye out. "Salt of Virtue" is an interesting expression; I wonder whether an analogy with salt as a necessity of life and as a preservative is implied.

(The Augustinian doctrine, as early as the twelfth century was expressed clearly in the books of Hugh of St. Victor and widely disseminated in the following century by anthologies, had certainly been drawn on by Bartolomeo di Bartoli, who took it without changing anything, except that he replaced Humility, the root of Virtue, with Discretion, the mother or salt of Virtue, which is probably the ability to discern good from evil, Virtue from Vice.)

There is a certain irony in that the ability to discern good and evil was what the serpent gave Eve in advising her to eat the fruit of the tree; now that same ability is the mother or root of good, as we will see when we get to the family tree.

This quote from Dorez was from Chapter V. There and following he gives ample justification for thinking that Bartolomeo's codex was in fact used as a book of models for various other manuscripts as well as frescoes and other artworks in Italy. Whether I will get to his examples remains to be seen. For now, we are still in Chapter IV. Dorez now turns to the next page of the manuscript, Folio 1L.

This next part is fairly boring. I include it because what comes after is interesting, and also because it shows Bartolomeo's Augustinian perspective, which he will apply to the virtues.

Folio 1L- This introductory page is devoted to the canonical Scriptures. It is divided into eight compartments, where they sit on simple wooden chairs, presenting their papers, six bearded characters: Moses, St. John the Evangelist, St. Ambrose with the bishop's miter, left; Ezekiel, St. Paul, and St. Gregory, with the papal tiara, right. In the center, the portrait’s proportions give the place of honor to the distinguished Doctor Augustine (white miter embroidered in gold, white robe and blue cloak lined with red), under which St. Jerome in his study sits with the usual cardinal's hat. All the doctors and prophets, Ezekiel and St. Jerome excepted, turn their eyes to the bishop of 'Hippo.I interrupt so that you can look at my poor photo of the illumination in question.

I continue:

24 LEONE DOREZIn this case GoogleTranslate didn't produce complete nonsense. So here is my attempt to get it in English:

Moses (Sizzurra [Tonsure?}. And red cape) carries several books, of which here are the Titles: Deuteronomi (sic), Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numerorum.

In the hands of St. John (green robe, red cape), we find his scriptures, i.e. Gospel, Epistles, Apochal[y]pse.

Ambrose, adorned in episcopal garments (white miter, white robe and blue cape), holds a scroll on which is written Hunc in Christo genui.

Ezekiel (green robe and blue cloak) also has before him a roll spread out, on which we read: Hic erat divisio discurrens, animalium splendor, ignis.

St. Paul (red robe and brown mantle) wields a naked sword with his left, while his right hand rests on the codex of his Epistles.

St. Gregory (papal tiara white embroidered with gold, red cloak lined with blue cloth) explains a large roll that bears this sentence: Si delicioso pabulo cupitis saciari, opuscula Augustini legite et ad comparationem illius nostrum furfurem non queratis: a very rare and truly pontifical example of literary modesty!

St. Augustine, covered with all the trappings of bishops (blue robe with folds of red cloth) holds in his left hand, pointing with his right, a roll on which are written these words: Non meo vel ingenio vel merito, sed Dei dono sum, si quid laudabiliter sum.

St. Jerome (brown robe and red cap) holds in his right hand and indicates with the left a roll where is recorded these words: Ecce quicquid didici potuit et sublimi ingenio de scriptarum scientiarum harum fontibus you positum atque dis[s]ertum (?).

The stanza contains its proper invocation to St. Augustine, whose works precisely on this page are starting to provide the above mentioned headings.

TEXT OF THE SECOND STANZA

Augustinus in epistola ad Jeronimum: Scripturus cunonicus solus ita ut sequor scriptores earum nichil in eis omnino errasse vel non fallaciter posuisse dubitem.

Oi, Agustin, cinto de la gran stola

Del Spirito Santo, a mi de la tua pace

Dame, doctor verace,

Sì che i tuoi testi a mi facian rubriche,

E le mie rime amiche

Siano a Moyses, Zechia (24) e Polo

Et agli altri che volo

Fanno a la rota et al bel san Ziovanni ;

Sì che di facti ossanni

Comprehenda alquanto qui chome un di schola,

Et al tuo fil mia spola

LA CANZONE DELLE VIRTÙ E DELLE SCIENZE 25

Sempre se tegna a far tela tenace.

E i tri doctur mi piace

Anchor preghare; a ciò che le mie spiche^

D'ogne mal far nemiche,

Meglio gharnischan; chi preghin ti solo

Che me condughi a volo,

Che possa le Vertù ponere in schanni

E le Scientie in panni,

Ch'el le cognoscha in vulgar chi n' à voglia,

E chi non pò de scriptura aver zoglia.

Oi, Augustine, surrounded with the great stole[/quote]

Of the Holy Spirit, give me peace

Give me, true doctor,

Yes your writing makes headings [rubrici] for me,

And my rhymes friends

Let Moses, Zechia and Polo

And others that fly

Make the rotation and beautiful St. John;

Make Hossanas to you

Understand somewhat of a choir here chome,

And to your thread my spool

THE SONG OF VIRTUES AND SCIENCES 25

Always make my canvas tough.

And I like the three doctors

Again asking; how my spikes

On all sides make the wrong enemy

Better gharnischan, who will only want

To teach me to fly,

What the virtues can put in schanni

And the Sciences in cloth,

That knows in the vulgar what it wants,

And that does not have some scripture zoglia (on the doorstep?).

I have no clue what "chome" and "schanni" mean.

Now comes something visually relevant to the tarot, an illumination with the four evangelists around a circle, with a lady on top of the circle holding a disc. I speculate that this image could one inspiration, first, of the Charles VI World card, with a few changes (removing the evangelists and putting hills inside the circle instead of the book), and then the Sforza Castle World and the Marseille after that (putting one of the upper figures inside the circle and restoring the evangelists). Actually, there is not much original here. Putting Christ or Mary inside a circle or almond was already standard practice, and at least with Christ it was also standard to put the evangelists in the corners outside the circle or almond. Bartolomeo is giving a doctrinal context for the image, using both the female Theologia and the male Christ. I am not, to be sure, maintaining that the lady in the various "World" cards is Theologia.

First, here she is, in the Chantilly Codex:

And here is Dorez's explanation. I include my attempt to translate the stanza (except for the Latin, of course).

Folio 2 r. –Later in the book (p. 55) Dorez gives us another example of Theologia from a different Italian manuscript of this time, Bibliotheque Nationale Ital. 112. He doesn't talk about this image in particular, as far as I have noticed. He just gives a general caracterization of the manuscript, as one probably on the Augustinian side of a great competition between the Augustinians and the Dominicans at that time.

On the top of the sheet, from outside the fixed limits of the illustration, shines the majesty of the bust of Christ with a halo in a blue background, and surrounding the figure writings with these words: Omne Datum Optimum et omne donum perfectum desursum est des[c]endens a Patre.

Under the extract of St. Augustine, from the triple rim of a wheel, is Theology, crowned and covered with a white coat with a buckle on the neck; her eyes turn toward Christ, raising in her left a small mirror, whence burst red rays which are reflected in the semblance of the Redeemer: Sapientia. On her right, descending along her body, the woman has another mirror, blue and white: Scientia. The related stanza explains that Theology ascends on two mirrors, gold and silver (which light in their turn the whole circle), to the great light, that is, to the glory of Christ.

The four animals symbolizing the Evangelists surround the circle so as to lift up Theology (onde la Teologia si solleva); the miniaturist has with unhappy artifice wanted their wings to intersect each other's, and it is a representation which isn’t pleasing to the eye; the painter may have wished to touch the sublime and has succeeded in falling into awkwardness.

The first circle of the wheel reads: Testamentum vetus; in the third- Testamentum novum, in the intermediate: Sensus litteralis, sensus moralis, sensus naturalis, sensus anagogicus, sensus ystor[i]ografus sensus allegoricus. In the open book that covers the hub of the wheel is written Ezechielis primo. Appararuit rota una super terram Habens quatuor et facies opera quasi rota in dimidio rote etc.

The two mirrors symbolize the two lights with which we can and must be interpreted the Bible and the Gospel, those of Wisdom and Science.

The six “senses” then are those that fulfill the hermeneutic interpretation of sacred scriptures. You may notice that the author adds two senses to the four already held up by his teacher St. Augustine in the first book of the Commentary on Genesis, that is, the way of nature and the way of the historiographer.

26 LEONE DOREZ

In these two sheets (1 t. And 2 r.) one will perhaps be allowed to recognize, beyond the knowledge of the poet himself, the inspiration given by Francesco da Prato, in the company of whom in the church of San Barbaziano, Bartolomeo corrected and revised the text of the Decree of Gratian transcribed by brother Ugolino Adighiero da Castagnolo.

TEXT OF THE THIRD STANZA

Augustinus in epistoia ad Macedonium: Hunc amavi et quesivi et eam (sic) a iuventute mea amator factus sum forme illius. Ex ipsa Sapientia que vere est una, si quid a Deo Sumpsi, nom a mea presumpsi.

Contempia questa donna el fin cristallo

In chi M divino amor tutto respiende,

E del gran lume accende

Dui richi spicchi ch'in man ten la damma.

E l'uno e l'altro infiamma:

Prima quel d'oro e poi quel de l'arzento,

Sì eh' ogne Testamento

Ghiar ce dimostra per sensi in la rota.

E Ila minor dinota

Quei ch'alia grande fan de penne el ballo;

E ciò che nel metallo

De luce appare, in lo cerchio discende.

Theologia m'intende

Ben quel eh' io narro, e so eh' ella ce chiamma

A quel che ciaschun amma

Et o' dovemmo havere el nostro intento;

Ch'el solo è '1 compimento

De le Vertuti e dan l'eternai dota;

Onde Prudentia, mota

Da bon pensier discreto, piegha el chollo

In quel per triumphar chol sommo Apollo.

(Contemplate this lady and her fine crystal

In which divine love all respiende [breathe, return?],

And the great light illuminates

Two rich mirrors in the hand of the lady.

And the one and the other ignites:

The first of gold and then that of silver,

So that every Testament

calls this demonstration of the senses in the rotation.

And the lower denotes

Those big of feather and dance;

And what in the metal

Of light appears in the circle descends.

Theologia understands

Well what I relate, and I know that there she invokes

What each one loves

And has given us his meaning;

That he alone is carrying

The Virtues the eternal endows;

So that Prudentia, mire [mota, possibly for moto, cause]

Of good discreet thoughts, bends the neck

In order to triumph with supreme Apollo.)

È infatti cosa assai curiosa a notare come le due serie di rappresentazioni delle Virtù e delle Scienze si presentino quasi un episodio caratteristico della rivalità fra gli antichi e i nuovi ordini monastici in Italia. La prima di queste due serie, più tradizionale dell'altra, è nata sotto l'ispirazione quasi esclusiva di sant'Agostino e de' suoi monaci ; la seconda, più nuova, più svariata, uscì dalla dottrina largamente interpretata di san Tommaso e de' successori del dotto Aquinate.Even its Augustinian character is not sure. The only things to indicate that are first, the close affinity to the Chantilly codex (p. 56); second, the number of times Augustine is cited, and how he is cited (p. 56); and third, its citations of two authorities, Richard and Hugh, probably two Augustinian monks at St. Victor in Paris but possibly two Dominicans, one in Oxford and the other at St. Cher (p. 57). All had written on the virtues and vices.

Nella prima l'ispirazione è più semplice, più conforme ai dati dei secoli precedenti. Esistono di essa in Francia almeno due monumenti ragguardevoli, il nostro codice cioè ed il manoscritto Italiano 1 12 della Biblioteca nazionale. In essi le Virtù e le Scienze sono separatamente rappresentate...

(It is very curious to see how the two series of representations, Virtues and Sciences, will present almost a typical episode of rivalry between the old and the new monastic orders in Italy. The first of these two series, more traditional than the other, was born under the almost exclusive inspiration of St. Augustine and his monks; and the other, newer, more varied, departed from the doctrine of St. Thomas, broadly interpreted, and the successors of Aquinas.

The first inspiration is simpler, more consistent with the data of earlier centuries. It exists in France in at least two notable monuments, our codex and that of Italian Manuscript 112 in National Library. In them the Virtues and Sciences are separately represented...)

In any case, here is the image from Ital. 112, which Dorez calls "Theologia and the Seven Virtues":

I see a comparison to the Cary-Yale World lady, there identified by her trumpet with Fama, in the sense of Gloria.

Manuscript Ital. 112 may also have been a model book. I don't know how frequent this particular pose was. I only know it in one other work,a Lombard painting of the 15th century (Vogt-Leurssen says it's Bianca Maria Visconti and her children, an hypothesis that here is only relevant for the time and place of origin):

I posted this image at http://forum.tarothistory.com/viewtopic.php?f=11&t=365&p=4839&hilit=sapientia#p4839, comparing it to the CY Fama lady. I didn't know then about the earlier manuscript image. Christ, as Sapientia, the German Weisheit, was portrayed similarly, as you can see at that post; he is also on some World cards, i .e. the Vieville (at right below) and probably the Sforza Castle card; there are even traces of this masculine image in the Noblet.

No comments:

Post a Comment