There is one major work on this manuscript, that in Italian of Leone Dorez in 1904, La canzone delle virtv e delle scienze di Bartolomeo di Bartoli da Bologna, testo inedito del secolo XV tratto dal ms. originale del Museo Condé a cvra di Leone Dorez (Bergamo Istitvto Italiano d'Arti Grafiche Editore, MDCCCCIIII). All other sources limit themselves to short summaries of Dorez and occasional disagreements. This work is online in Italian but has not to my knowledge been translated. So I present here the relevant portions of Dorez, with occasional comments, translating his Italian to English. I will not translate his transcriptions of the Latin material in the codex. I am using the digitalized text at http://archive.org/stream/lacanzonedellev00bartgoog/lacanzonedellev00bartgoog_djvu.txt, which I have compared to the original hardcover book, run through translation machines and dictionaries, and fixed as best I could. I am by no means fluent in Italian, and that Bartolomeo's medieval terms are particularly problematic.

In this first post I will give you my translations, such as they are, of the first three chapters, pp. 9-23 of Dorez, along with reproductions of the illuminations he is talking about and a few comments by me. I include the page numbers and headings at the beginning of each page. Comments in brackets, usually giving the Italian when I think it might be important, are mine, except that comments in brackets about the Latin are Dorez's.

9 DOREZ

I. HISTORY OF THE CODEX.

Of the most admirable collection of codices in the sumptuous library of the palace of Chantilly of the venerated memory of the Duke of Aumale, the volume holding the chief place is that in which we read, transcribed and illustrated, a moral song, dedicated by Bartolomeo di Bartoli da Bologna to Bruzio di Luchino Visconti. ' although of interest for those who study the literary tastes of one of the roughest bastards of the house of Visconti, it is of most importance for the history of Italian art at the end of the Middle Ages.

It can be said without exaggeration that no relic more deserves to be fully reproduced by the workshop of the Italian Institute of Graphic Arts. We hope that archeologists do not judge our labor in vain, but on the contrary to be of no little utility for those studies of art that will certainly be accomplished, as one from the century passed away just now, to that just begun.

Before turning the notices one could find, in chronicles and documents of the time, of the author and the owner of the work to which we are dedicated, it is appropriate to say where this precious volume was conserved, at least in the eighteenth century. First to discuss them was that diligent investigator of the literature and history of Milan Argelati Philip, who in his Biblioteca writes thus: "But why we speak of Bruzio Visconti, we believe it is to gratify scholars, pointing to a codex in parchment, elegant, in folio, preserved in the Archinto library, full of excellent miniatures made in gold.At this conclusion of Chapter One, I interrupt for a comment. So we learn that at least in the 18th century, the work was still in Italy. Here is a version of that miniature, which Dorez will discuss in detail later:

10 DOREZ

"It has this title: Incipit Cantica ad gloriam et honorem magnifici militis domini Brutti nati incliti ac illustiis principis domini inchini Vice-comitis de Mediolano, in qua tractatur de Virtutibus et Scientiis vulgarizatis, Amen „. - Thus Litta compiling his Famous Italian Families of c. 1820, obtained from Count Archinto communication of the poem by Bartolomeo di Bartoli, and it was valued for its reproduction in color, not too happily, however, of the first miniature, really magnificent, which represents the author kneeling before his patron. And the Archinto volume remained at his house until the day, now long past, when one Robinson of London, the agent of the noble Milanese family, sold it to the Duke of Aumale.

I resume at the beginning of Chapter Two:

11 DOREZSo now we may begin Chapter Three:

II. BARTOLOMEO DI BARTOLI

It is easy enough to find the name of the author, since he himself identifies himself in the sending [invio] of his song. He speaks thus:

Bartolomeo da Bologna di Bartoli

My faith ' [Me fe’], because I am Catholic, [perch’io m’incartholi]

With poor [miser] Bruze, and make it to be painted for him.

What is less easy to identify is the success achieved by this writer, rather obscure, which seems strange to all historians of Italian literature. The song is actually something so unremarkable, so devoid of poetic inspiration, it is no surprise that it soon fell into oblivion as the ramblings of not one of the 'minor poets,’ but the least. But it is because happy Bartolomeo, compared to many others, made so artistically "depinzere" a composition so mediocre. The work of the brush has saved that of the pen.

Bartolomeo di Bartoli was one of those calligraphers, not entirely without culture, who by wealthy lords or convents sometimes made most splendid manuscripts. We by chance find four of these codices transcribed by Our Author: in addition to the Chantilly, there are two that show us his associate the famous miniaturist Niccolo da Bologna. Of all we give here a succinct description.

1, (Year 1349). First is the '"Officium sancte Marie Virginis", which now belongs to the Benedictine Abbey of Kremsmünster in Upper Austria. At the end of the last page (82 t.) it reads: “Ego Bartholomeus de Bartholis de Bononia scripsi hoc officium sancte Marie Virginis. Anno Nativitatis Domini millesimo trecentesimo quadragesimo et nono, indiciione secunda, die martis XXIIIL In vigillia Beate Virginis explevi. De mense Martii.”

At 83 t. follows the Officium in peragendo mortuorum (sic), which finishes at 184 t. with the subscription: Finito libro, refferamus gratias Christo, Qui scribit scribat. Domino semper cum Domino vivat. Vivat in Celis Bartholomeo. In nomine. Amen. The miniatures of this codex are by Niccolo da Bologna.

12 LEONE DOREZ

2. (Year 1374). The second was part of the Palatine in Mannheim, and now is conserved in R. Library of Monaco of Bavaria (Lat, 10072). It is a Missale secundum consuetudinem Romane Curie, where page 360 r. reads: "Explicit officium Missalis secundum consuetudinem Romane curia, Deo Gratias Amen. Correctum et postscript per me Bartholomeum de Bartholis di Bononia scriptorem. MCCCLXXIII, indictione XII, XXIII Februarii." The first miniature, of which Valentinelli has given a detailed description, that of p. 161t.-162 r., bears the name of NICOLAUS DE BONONIA, and also gives him as the so-given author of the two hundred initial letters, containing groups of figures from the Old and New Testaments, as well as the lives of Saints that seemed to be made by the same painter."

3. (No date). In the Chigi in Rome (LV 167) the Viscount Colomb de Batines has found a “codex of the Divine Comedy in 4 ^ parchment. of XIV century (about 1370), in big round Gothic characters, with titles and topics in Latin in red ink, and embellished initials in color for each song, and otherwise bigger at the beginning of each canto, and conserved most beautifully". At the end it reads: Explicit tertia Cantica Comedie Dantis Aldigherii de Florentia, in qui tentat [tractat?] de Gloria Paradisi. Ad quam anima cuius [eius?] et omnium fidelium per misericordiam Omnipotentis Dei Requiescat in pace. Amen. Ego Bartholomeus de Bartólis scripsi. Said de Batines: "The amanuensis also puts his name after the subscriptions placed at the end of the first two Canticles." * Perhaps Bartoli transcribed that example of the poem when Benvenuto di Buoncompagno began publicly to read Dante in Bologna about the year 1369.

4. (No date). Finally, the Paris Nationale, a few years ago, recovered a copy of the illuminated Decretum of Gratian, which belonged to President Bouhier, of whom the final subscription says: Explicit textus Decreti. Deo Gratias. Correctus per dominum Francisscum (sic) de Prato et Bertholomeum di Bertoli in ecclesia de Bononia Sancii Barbatiani. - Frater Adigherius condam Ugolini de scripsit Castagnolo. (Nouv. acq. lat. 2508). The first part of that subscription is certainly the hand of Bartolomeo di Bartoli, as can be assured by comparing the facsimile reproduced here (see Plate II) with the codex of Chantilly. Also from this subscription, like that of the Missal of Monaco of Bavaria, Bartoli is not satisfied with modest glory as an elegant writer, but also aspired to the reputation of diligent editor. Who will make a critical study of the text of the Decree and the Roman Missal, so as to decide whether this pretension of Our Author was well-founded.

That's all that has been found about the person and work of the Bolognese writer and corrector. Others will perhaps be more fortunate than we. But it is possible to observe some relevant considerations. Bartolomeo has written with obvious pleasure the work

THE SONG OF VIRTUES AND SCIENCES 15

of Alighieri; Whence one can perhaps infer that he had some relationship with the homeland of the poet, which, as we shall see later, would be of little moment for the history of the Codex of Chantilly. That could be more of the subscriptions of the codices of Kremsmünster, Monaco and Munich and Paris, as well as from the collaboration of Our Author with Niccolò di Giacomo da Bologna, to argue that he never left his native city, but there always exercised constantly his profession. And even that is not without interest for the genesis of the song to Bruzio Visconti.

16 DOREZ

III. LUCHINO AND BRUZIO VISCONTI

According as he is found responsible for the title of the song sent to him, Bruzio was the son of Luchino Visconti, brother of the celebrated Giovanni, Archbishop of Milan. Luchino, like all other members of his family, believed he had good friends on the part of the poets, who perhaps did not make much account of him. Fazio degli Uberti, to whom he had addressed a petition with a sonnet, unfortunately obscure, he replied in kind with an essay that If the art is poor, it is at least not ignorant of courtesy [é povero d’arte, non é meno digiuno di cortesia]. They want Petrarch as well to be clutching at ties of friendship; all that is certain is this: in 1347 he asked Messer Francesco to send 'verses and seedlings collected in the garden of Parma, and that the poet one day care to satisfy him by sending him a letter with particles from the floor and a 'poetic epistle.’

Somewhat later, Petrarch addressed another metric epistle to Luchino, in which he praised Italy, urged the prince to take due account of letters, and cited the example of several ancient captains, among whom can even be noted Nero.

Also Fabrizio or, as he is known to contemporary writers, Bruzio Visconti, Luchino's favorite son, had literary relations, even more familiar than this same Luchino, with Fazio and Petrarch. It was certainly not flour to make communion wafers the man who with so much greed tyrannized and oppressed the poor town of Lodi, entrusted to his care by his father, who, when he died, January 24, 1349, he did not dare any longer against Genoa, which they had been besieging, or return to Milan orelsewhere in Lombardy, and sought refuge in the Veneto. His father, though a military man, exceeded him in moral virtue; from Azario and Flame he comes to us pictured as austere, generous, just, charitable. The blind love he felt for his son, who obtained all that he craved and had thus become tacitly "second Lord of Milan,” perhaps caused Bruzio's more serious perversion.

While he held Lodi, Bruzio led a great life and spent without counting. "He took a wife from Castelbarco, of the Trento region, and like Nero ruled the city. The people dared not speak. He was not

THE SONG OF VIRTUES AND SCIENCES 19

dressed, as the Gospel says, in the wedding garment. He carried off whatever he wanted. Not with more justice, was everything done according to his wishes, because he was reputed smart, clever and knowledgeable. Everywhere he acquired moral books, and having good and reasonable princes, came to an awful end. Many beautiful things were said of his completed study.” Thus Tazario, who really gives us the clearest explanation of his dedication to Moral books Bartolomeo di Bartoli of that "bad company". The ruthless tyrant of Lodi loved books, and, with a phenomenal hypocrisy, affected to read with special preference those which dealt with moral matters. And indeed is preserved the Nationale in Paris further proof of his taste, that is, a codex surpassing even the Chantilly, dedicated to the same Bruzio by Luca de Mannelli, a Florentine of the Dominicna order, of whom we will later have occasion to speak at greater length.I interrupt now to show my poor photos of Dorez's Plate III. First the top, in which you can see some of the thirteen cities as well as Bartolomeo presenting the book to Bruzio, Then the bottom.:

Meanwhile, here is the original title of the volume {Lat. 6467, and. 2 t.): Incipit compendium moralis philosophie. P. 13 t. reads:"Incipit traciatus de quatuor virtutibus cardinalibus"; At p. 45 r.: Tractatus de amicicia and 52 r.: Explicit opus breve moralis phylosophie compilatum per Reverendum virum fratrem Lucam de Manellis ordinis Predicatorum. Deo Gratias. Amen. In the dedication Marinelli said he had completed his treatise on the orders of his master: In hac Inquam philosophia moralis a mi vestro familiari compendiosum Silvestro et clarum rogatus tractatum...

And a little further: Ne vero arrogantiam asscribatur mihi quod scribe possem causam reprehensionis in Vobis referre; \ na \ m si insipiens factus sum sapientium usurpans officium, Vos, domine, me coegistis, Dominorum enim rogamina etiam is supplicent coguni Sed aliam excusationem effero, quia quicumque hoc opus culpare voluerit cognoscat quod hoc opera expressi ab Aristotle ex libro Ethicorum ab ex, ex libro de Tullio et Officiis Tusculanis questionibus a Thoma ex prima et secunda secunde college, pauca de meis cogitationibus praeter formam procedendi subiungens, et ideo non me, sed supradictos auctores ledit, qui has sententias depravare conatur.

Among his authorities Luca again cites the text of the work of Seneca and St. Augustine. Moreover, this compendium, which as materially as literarily is mediocre, this obscure book would be of little value, if not preceded by a beautiful frontispiece representing Bruzio, the author, thirteen major cities of Lombardy in many small medallions, and again, in the middle of six of the ancient authors and saints, Bruzio as the figure of Justice trampling Pride. A painting that is certainly not entirely consistent with the historical truth, but it has emerged from the brush of Niccolò da Bologna, who we recognized have collaborated with Bartoli. (See Plate III).

In the center we see Bruzio as Justice overcoming Pride.

Now I resume my translation of Dorez:

Much more educated than the father, whom Petrarch wrote in the epistle of 1347, urging him to love poetry, in the poem sent to him along with seedlings:I am not sure what a "Zoilo" is. Lorredan on Tarot History Forum sugests, without being certain, that it is a "firebrand, quick to flame." If so, it would seem an apt description of the arrogant Bruzio.

20 LEONE DOREZ

"You have tasted the first fruits of letters," Bruzio was a "true man of letters and not at all a mediocre poet" as demonstated in his poems, diligently published and studied with great acuteness by Renier. Also to him Petrarch wrote a "letter that reads in poetic stamp entitled to a “Zoilo ** with or without title, and in the codex [Strozziano 141, ed. 64, in the Laurentian of Florence **] bears instead: Epistle ad dominum "Bruzum de Vicecomitibus Mediolanensem, but "not bearing courtesies,” in a response of the Tuscan poet to the satires directed against him by Visconti. Likewise Fazio degli Uberti addressed a sonnet to Bruzio which boasts his loyalty to him:

“King Arthur, or any other aspect of time; [El re Artu,né altro tempo aspetto]But in the existence of a Visconti tyrant, poems and moral treatises are incidental and a luxury, nothing more. In real life, the passion of an imperious man remains his policy. Probably in 1355, tired of the obscure life that since 1349 he led in the Veneto, Bruzio was in Bologna, where he was amicably greeted by his cousin, John Oleggio, captain and governor of the town, who, lacking faith in Matteo Visconti, on his part Maltraversa and Ghibelline, had just begun his rule himself.

All are given the love that I say to you,

In order that [Ond’] I have you as lord and friend."

Between the two, joint friendship did not last long, for, after the death of Matteo, which occurred September 29, 1355, Bernabo Visconti devised to tear Bologna from the hands of Oleggio, and to make sure, he knew the connivance of Bruzio. Who no doubt very carefully hatched the conspiracy, and was a cousin. He was provisionally arrested in February 1356 and expelled from the city "with only his clothes" [colle sole vesti] as a "dog". Again he fled to the Veneto, in a place Azario called "Achatum" (perhaps Cattaio, or better Cat, in the province of Padua), where he died in the troubles of extreme poverty. We will see later what import these circumstances bear on the history of the Chantilly Codex .

Let us continue with Dorez. We are the beginning of Chapter IV:

IV. DESCRIPTION OF THE CHANTILLY CODEX.I must interrupt this translation briefly so as to address the riddle about the manuscript's reference to Luchino Visconti as a key to the dating of the work. This first bit was written before Luchino's death in 1349, but then his name was scratched out; so it wasn't turned over to any Visconti until after 1349. Given that Bruzio is the consistently named dedicatee, and that he was nowhere near Bologna, after his father's death, until 1355, this deliberate cancelation must have happened after 1349. When the codex was completed is another matter. I don't know whether the mention of Luchino means that it was started while Luchino was alive but completed later, or that it was completed before Luchino died. Scholars since Dorez have decided that it was completed before Luchino's death, i.e. 1339-1349; see Julia Haig Gaesser, The Fortunes of Apuleius & the Golden Ass, p. 84, at http://books.google.com/books?id=fOq28aY4QUUC&pg=PA84&lpg=PA84&dq=Bruzio+Visconti&source=bl&ots=4Ev2ONc8tZ&sig=8osj2GywW-Ln8w-LDIRfGSsiVG8&hl=en&sa=X&ei=si4iUKOqLfP9yAGepYDIDg&ved=0CHQQ6AEwDA#v=onepage&q=Bruzio%20Visconti&f=false. She cites p. 560 of G. Orlandelli, "Bartolomeo de' Bartoli," in Dizionario biografico degli Italiani 6 (1964), pp. 559-560. But I am not convinced. Bruzio wasn't "miser Bruzio" until after 1349. Perhaps Dorez will have more information.

It is now time to describe the precious codex of the Museo Condé.

The format is in folio (0.333x0.226), written on parchment, and tied in red velvet; it consists of 20 pages, adorned with 20 large watercolors and painted initials. The rubrics are in Latin, the text Italian. Here's the title: [i] Incipit cantica ad gloriam et honorem magnifici militis domini Brutii nati incliti ac illustris domini principis Luchini (this name was deliberately canceled) Vicecomitis de Mediolano, in qua tractatur de Viriutibus et Scientus vulgarizatis. Amen.

I continue. Here I translate the Italian word "stanza" as the English "stanza" rather than its usual equivalent, "room", since each "stanza" is said to have 21 verses, which would not normally be true of rooms.

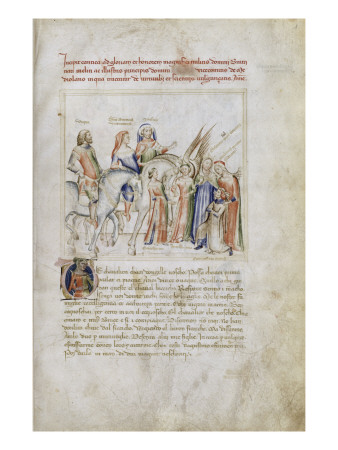

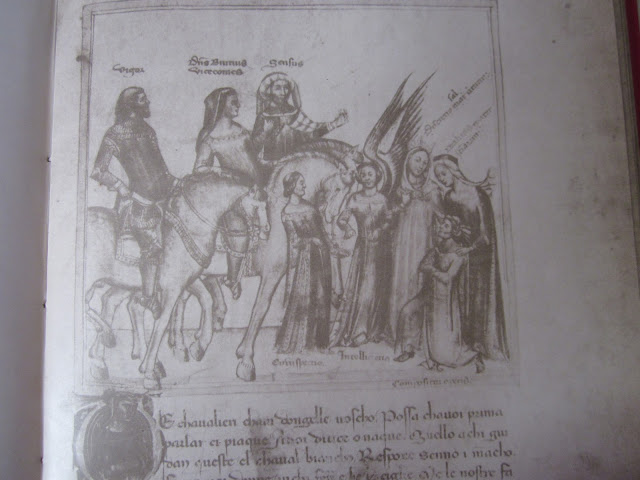

The Song is divided into two parts, each of which consists of nine stanzas, twenty-one verses each, and a coda (conogedo = discharge). The first part contains the description of Virtue, the second that of Science.I interrupt here to give this illumination. The one in color I linked to before, with poor resolution, is at

In the initial stanza the author declares his purpose, to describe in words of vulgar rhyme the daughters of Discretion, mother of the virtues, and those of Docility, mother of the Sciences. The second stanza contains an invocation to St. Augustine, from which will be derived the Latin rubric of each stanza of the song. The eight other stanzas are devoted to Theology, Prudence, Fortezza [i.e. Fortitude or Strength], Temperance, Justice, Faith, Hope and Charity. The first part ends with the coda, before which, as a kind of summary of everything, is a family tree.

The second part describes the Sciences: Philosophy, Grammar, dialectic, Rhetoric, Arithmetic, Geometry, Music, and Astronomy or Astrology. It ends, like the first, with a coda in which the author is named (Bartolomeo da Bologna di Bartoli), adding that he painted this volume for Messer Bruzio Visconti.

Each of the pages devoted to Virtue and Science is divided into three parts: on the top is transcribed the definition of the Virtue of Science, extracted from the works of St. Augustine; in the middle is seen expressed in color the representation of the Virtue or Science; the last, on the bottom, has the stanza dedicated to the Virtue or Science itself.

22 LEONE DOREZ

PART ONE - The Seven Virtues.

Folio 1r. - Under the title of the work, with marvelous art, is a scene, in which you see at left, three knights, the first called Vigor, the second Dominus Brutius Vicecomes; and third, with the doctor’s cap, Sensus[Judgment, Good Sense]. Before the horse of Bruzio are two women, Circumspectio (mantle in red and green, edges blue, green wrap around her head), and Intelligentia [Intellect] (dressed like her neighbor, except the edges), the latter supplied with two large wings, guiding the bit of the horse of the young Visconti in front of whom a man is kneeling, the compositor operis, Bartolomeo di Bartoli. Next to him are found two other women: the first, with the crown on her head, is Discretio, mater or sal Virtutum (white veil, blue robe and green mantle), the second, older, who puts her left hand on the shoulder of the poet, is called Docilitas, mater Scientiarum (red dress with blue sleeves and green cloak, headpiece red and white).

http://www.allposters.it/-sp/Chansonne-des-sept-Vertus-et-des-sept-Arts-liberaux-destinee-a-Bruzio-Visconti-Posters_i7303658_.htm. My black and white photo--not very good but the writing can be made out, is below:

As there is sometimes discussion of why, in the tarot, only Temperance has wings, be sure to notice here that out of these three primary virtues--Intelligentia, Discretio, Docilitas--only one, Intelligentia, has wings. It is not even the most important virtue, who as mother to the rest would be Discretio. I see no general convention as to the giving of wings. I resume.

The first knight, Vigor, on a dappled horse, has long hair, full beard, and above his coat of mail wears a robe half red and half green. One who compares this figure with those famous portraits that have come down of Bernabo Visconti (and particularly the famous equestrian statue admired under the portico of the Ducal Court in the Castle of Milan) will not hesitate to recognize here represented the future husband of Queen Della Scala. If, as we believe, this identification corresponds to the truth, it is very important, as we shall see below, to determine the exact date of execution of our codex.This particular stanza of medieval Italian is too hard for me, perhaps because it is a colloquial dialogue. I don't think it matters much.The later stanzas I can more or less understand, but not this one.

Of a very gracious face and attitude is Bruzio Visconti, who, beardless, of almost feminine beauty, his body a little back, head bowed and covered with a red hood that goes over the bare neck and shoulders, puts his right hand quietly on the back of Bernabo’s and his left on the neck of his own white steed. Of this horse the right leg, the only one that I can see, is very poorly designed, excessively long and rigid, as are the rest, as the front legs of horses almost always are in the paintings of that century.

The third rider, who wears on his head a white and blue doctor’s cap, under his red cloak a green gown, with the hems of the sleeves red, raises both hands in the act of speaking. Who is this doctor of laws? Almost certainly we can identify him as Franceschino de' Cristiani, a Pavian judge, who in 1349 was sent by Luchino to assist the son in the siege of Genoa. In this expedition Rinaldo degli Assandri, a knight of Mantua, had acted as executor; the counselor was Christiani. So in the first we see the "Hand," and in the second, “Judgment.”

THE SONG OF VIRTUES AND SCIENCES 23

I said that the doctor raises his hands as a man who speaks, and in fact, as is clear from the first room of the song, he speaks to Discretion and Docility, who for their part want Bartolomeo di Bartoli to describe their daughters, that is, the Virtues and Sciences, to Bruzio. The poet, far from rejecting the offer, gives them full satisfaction, helped by texts extracted from the works of St. Augustine, to do the job he then will offer to the two Visconti:

Text of the first stanza.

"De, chavalieri, ch'avi dongelle voscho,

Possa ch’a voi prima parlar ci piaque,

A noi ditice o' naque

Quello a chi guidan queste el chaval biancho.”

Respoxe Senno: "I’ mancho

Senza voi, donne, in chi ferme ho le ciglie;

Mo le nostre famiglie

Intelligentia et Acchorteza parme,

E che Vigore in arme

Ben cognoschai; per certo in voi il cognoscho;

El chavalier eh' è noscho.

Chiamato è miser Bruze “; e si i compiaque;

Discretion non taque.

Né han Docilità chi v' è dal fiancho,

Vegiendo el baron francho;

Ma dissenme ambe due per miraveglie:

“Descrivi a lui mie figlie

In rima per vulgare”. E satisfarme

Conuen loro et aitarme

Choi testi d'Agustino e farmen ponti;

Poi darle in man di dui magiur Veschonti.

The interesting parts are yet to come. I think maybe I will get to one in my next post.

No comments:

Post a Comment